How do you say goodbye?

I wake to the sound of the wind in the rigging, not the shriek of a gale, nor the steady howl of a 25-know wind, just a gentle moaning that tells me the wind is rising. I should get up and check the anchor, I think sleepily. Then I remember the boat is not in the water, it’s up on stands in a boatyard, accessible only by a stepladder at the stern. Our loft apartment in Titusville, we call it, jokingly.

After a while you get used to the sounds of the boatyard—the whine of the travel lift, the roar of the pressure washer as the yard workers clean the scum off boats just pulled out of the muddy intracoastal waterway, a symphony of power tools, day and night—it’s a do-it-yourself yard. We call the young man on the boat beside us Dracula because he only works at night. Clearly he has a day job. I’m not sure when, exactly, he sleeps.

And you even get used to the sounds of the city—ambulances screaming by on the highway outside the boat yard—there’s a hospital about a mile up the road—cars racing by with their music blasting. There is a park beside us which is an endless source of acoustic amusement—the cheerful if not a little repetitive tunes of the ice-cream truck, bands that play late into the evening on weekends, angry shouting in the middle of the night which usually settles down when the police arrive.

What you don’t get used to is the way the boat sways on the stands in a heavy wind. Or how it shakes as freight trains rumble past in the middle of the night. Or the way the stand at the bow is slowly sinking into the gravel, giving the boat a bit of a lean to starboard. Boats really shouldn’t be up in the air.

But it won’t be for much longer. Tomorrow, a new owner will take possession of Monark, launch the boat, and sail it away. How, I wonder, do you say goodbye to a boat that’s been your home for more than twenty years?

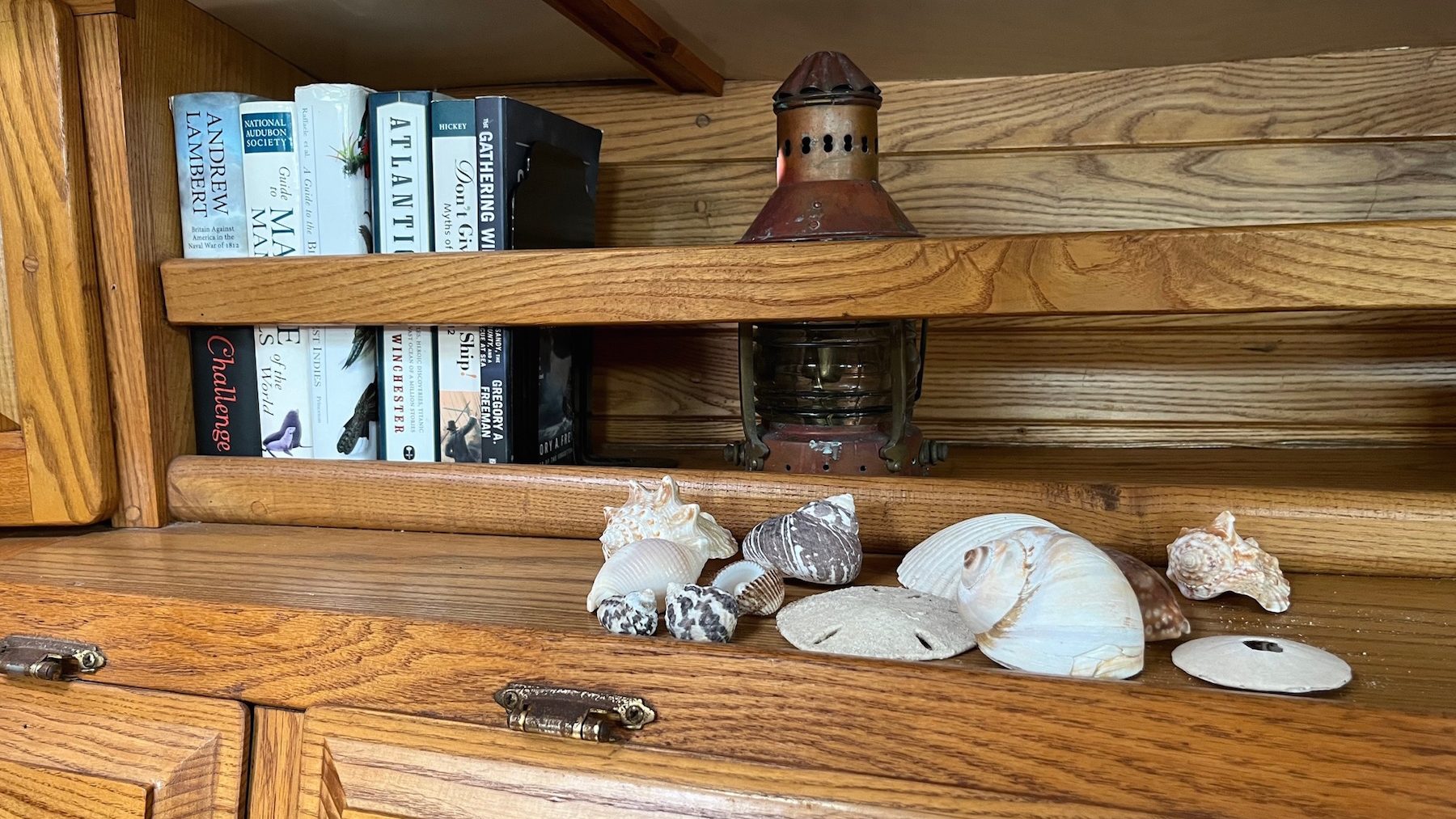

I look around the salon, at the leather cushions we had made before we set out, the wooden table Chris designed and built and I hand-rubbed with layer after layer of varathane. The shelves of books accumulated over the years, pilot books from around the world, a guide to marine mammals, a thick marine medical guide, consulted only occasionally over the years, thank goodness, but a welcome resource when I thought I might have to do a tracheotomy on Chris 25 miles off the coast of Cuba.

The lines are all neatly coiled and hanging in a row on either side of the companionway. I know each one by heart, can grab the main halyard or starboard preventer without thinking about it. The hours I’ve spent sitting at the top of the companionway, the most stable and protected part of the cockpit, sheltered from the salt spray as we pounded into heavy seas.

How do you say goodbye to all of that?

First you go through the lockers, one by one, sort through the accumulation of part rolls of masking tape and ball caps and out-of-date sun block, old flares, so many old flares. A true sailor, I’ve learned, never throws out flares, you keep the old ones, just in case.

You go through the food lockers, pack unopened non-perishables into a box for the local food bank, throw out the remaining half cup of rice in the canister, the long-expired box of crackers lying forgotten at the back of locker in the salon. You pack your clothes, discarding shorts and T-shirts so sun bleached or splattered with paint and varnish that they they’re unsuitable for return to civilized life. I slip a few things I’ve collected over the years into the suitcase, an olive bowl from Spain with a little pocket inside for pits; three small nesting bowls from Portugal, the perfect size for granola in the morning, a beautiful blanket from Mallorca.

I leave our shell collection behind, too fragile to transport, and anyway, a shell collection is not a static thing. You add to the pile as you find new treasures, oh this is much prettier than that one. What was I thinking? Over the side it goes.

When everything is packed, I will wash the cupboards inside and out, dust and polish the wood throughout the boat, clean the portholes, sweep and wash the floors for the last time, how many times have I crawled over them on hands and knees, getting myself stuck in awkward corners. I’ll take the bedding and towels to the laundromat, bring them back and put them away, neatly folded, still warm from the dryer.

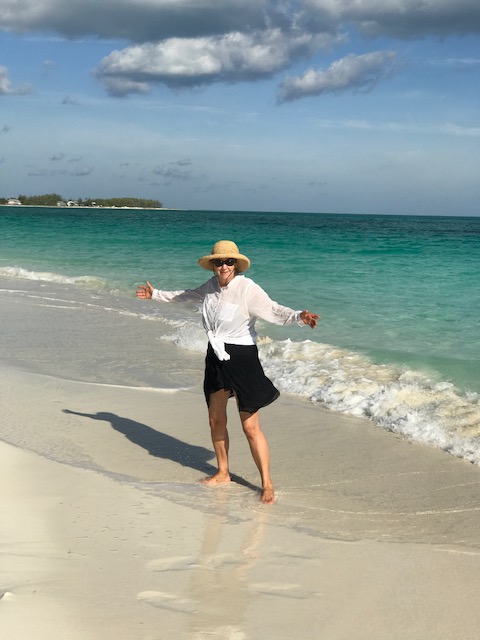

And then it will be time to go. We’ll climb down the ladder for the last time, stand at the stern, look up at the boat. Remember that anchorage off Mallorca, Chris will say? Of course I do, a single mooring ball off a tiny island way out in the Med, private no doubt but there wasn’t a soul around. It wasn’t so much an island as a huge rock formation, folds of limestone rising steeply from the seabed. It was uninhabited, and with its steep cliffs, almost entirely inaccessible.

Once we were secured to the mooring ball, we sat in the cockpit and watched a steady stream of shearwaters swoop in to roost in crevices in the rock, a chorus of loud cries, whether of greeting or protest I couldn’t tell, as each new arrival approached. Then darkness settled in and the birds fell silent and we were perfectly alone.

Ah yes, you’ll remind me, but do you also remember the time we got it all wrong? We were the only boat at anchor in a deep bay, almost a fjord, on the other side of Mallorca, tired after a long day of sailing. The wind shifted in the night and we had to pull anchor and beat our way out into the building seas and sail around the island in the dark.

Yes, I’ll counter, but then there was that beautiful anchorage in Little Basin just south of Cape Breton.

It’s time, you will say gently. We’ll look up at Monark for the last time, say a silent thank you, then get in the car and drive out the gate.