The sun is just coming up when I arrive at the first patch of meadow. I open the back hatch, grab my binoculars, set out my clipboard and instructions, my bird book, my water bottle. I’m ready to get started.

This spring I volunteered to survey several parcels of land for Wildlife Preservation Canada, looking for any evidence of loggerhead shrikes. Data gathered by volunteers like myself will help them carry out various recovery programs for the endangered species. But that’s not my only motivation—it’s nice to have an excuse to walk along the backroads of Bruce County on a sunny June morning.

A cow watches me from the other side of the fence. She lows softly. A greeting? A warning? She’s lying on the dew-covered grass, several calves curled up around her, all different colours—white, dark brown, one tawny like she is. Surely they’re not all hers. Perhaps its her turn to mind them. The rest of the herd is grazing quietly nearby, a half-grown calf follows one of them, nuzzles her when she stops, I want my breakfast too. The sun bathes them all in soft, yellow light.

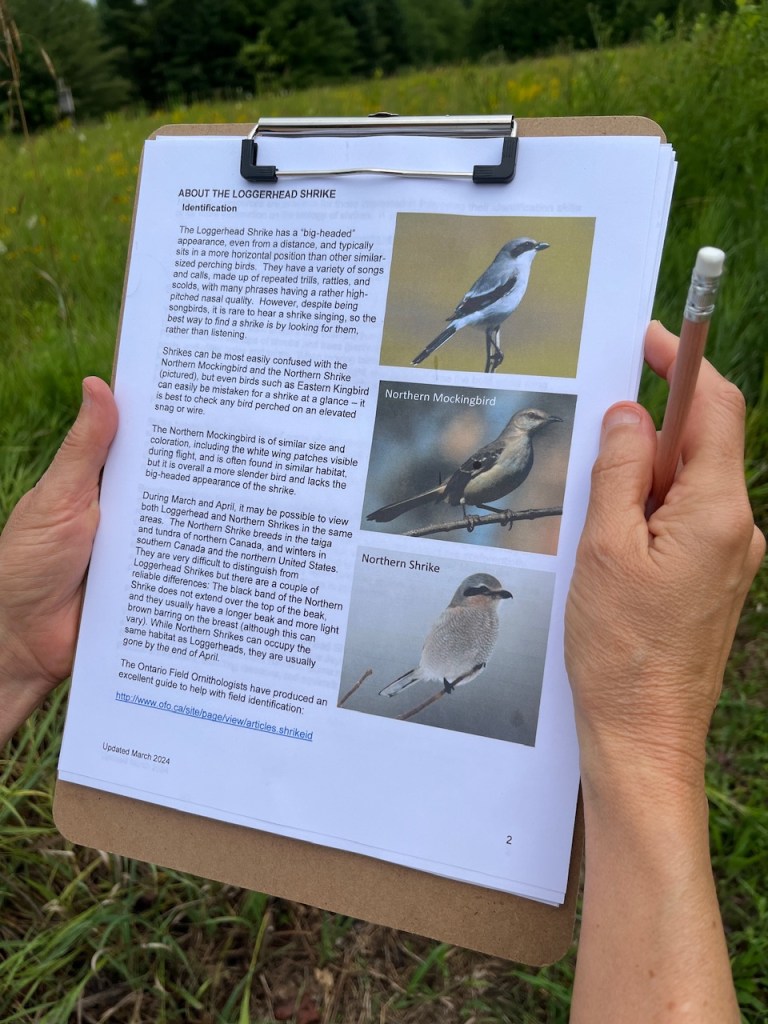

Oh yeah. Shrikes. I’m supposed to be looking for shrikes, not looking at cows. I record my start time then raise my binoculars and sweep the meadow, looking at places a shrike might perch—the top of a fence post or a tall tree, even a hydro line, any place they can scan the grass below them. They’re nasty birds, really—songbirds that act like birds of prey, swooping down to grab large grasshoppers, crickets, and dragonflies. They will also nab small snakes and mice, even smaller birds, but unlike a true bird of prey, they’re not strong enough to hold their dinner in their talons while they eat. Instead, they impale their catch on large thorns or barbed wire while they devour it, which has earned them the nickname “butcher bird.”

After ten minutes of scanning and seeing nothing but crows and a few red-winged blackbirds, I play the recording of a shrike call I’ve been provided. I wait another ten minutes.

No shrikes. I close the back hatch and move on.

The next stop is my favourite—several patches of meadow close to each other, easy to survey, I can walk along the road from one patch to the next. It’s the kind of habitat shrikes favour, too. They like to be near other breeding shrikes, but they also need enough room to raise their own young.

I start with the patch of land on the south side of the road, set up my equipment. The grass has grown quite tall since I was here a month ago. I eye it suspiciously—is it just grass, or is it a weedy crop? I can’t really tell from the side of the road, and one thing we’ve been sternly warned not to do is trespass on private property. But whatever is growing here is probably too tall to attract shrikes, who prefer short grass, which makes it easier to spot their prey before they pounce.

I record my start time, sweep my binoculars over the meadow. Crows. Red-winged blackbirds. And swallows, so many swallows, oh, barn swallows, a species at risk. I make a note, then watch as they skim the meadow.

There’s a deserted house in the middle of the field and I see one fly in through a missing attic window. What acrobats they are, I think as I watch a steady stream of swallows swoop in and out. They must be nesting in the rafters. I study the house, the front porch is missing, the small front windows completely obscured by bushes. Whoever built this house would have worked hard to clear the land one acre at a time, only to discover that the soil was too thin, too rocky, to grow much. I’m looking at a broken dream.

But I’m supposed to be looking for shrikes.

I turn to a patch on the other side of the road, rolling meadow sloping down to a creek lined with the kind of dense shrub shrub shrikes like to nest in, the occasional thorn bush here and there for them to impale their victims on. The presence of other meadow birds is encouraging. I can hear a meadowlark, two meadowlarks, singing their lilting song. A bobolink flits up out of the grass, which is a perfect length, not too short, not too long, grazed but not overgrazed. And even though it’s late June, the cattle haven’t been turned out yet. An enlightened farmer, perhaps? Allowing time for the ground-nesters’ young to fledge? Or perhaps just a farmer with enough land to support his herd. In any case, it’s perfect habitat for shrikes.

I lean against the car, take my time scanning the meadow. I watch a great egret working its way along the creek, then train my binoculars on each fence post, each tree top. Nothing so far. Time to play the recording.

The great egret leaves with a loud squawk. Sorry to disturb your peace and quiet, buddy. In the silence that follows, I hold my breath, surely… I catch a movement out of the corner of my eye, a bird emerges from one of the bushes, cocks its head at me. I try to convince myself that it’s a shrike but have to admit that it’s a grey catbird. Interesting call, he’s thinking. Perhaps I should add that to my repertoire.

I spend more time than I should walking along the road, scanning for birds, enjoying the feel of the sun on my back. Finally, reluctantly, I pack up and drive to my last patch, along a busy road and right next to a working quarry. I don’t expect to find a shrike here but must check just the same. Half-heartedly, I scan the rocky pasture. Last time I was here, there were cattle, too many cattle, grazing it to the ground. I spot a couple of crows. A red-winged blackbird flies overhead.

A pretty goldfinch catches my eye, perched on top of a fence post. Wait, what’s that, a little further along? A shrike-sized bird, eyeing the ditch. It swoops down, hovers over the long grass, ah, a king bird. I can clearly see the white band on his tail feathers

What an odd fence, I think, as I continue to scan it for birds. There are a few widely spaced fence posts, but between them crooked pieces of split cedar and rough branches have been stapled to the sagging wire to help support it. Not a well-kept farm, nor likely a very prosperous one. The cattle have been moved to the pasture across the road, if you can call it a pasture, searching for what grass they can find among the rocks. There is a muddy pond for them to drink from, or perhaps stand in on hot days. No trees. No shade for them. Who is more endangered, I wonder, as I pack up my gear: the shrikes or the farmers trying to eke out a living on this marginal land.

I find myself thinking about the family that homesteaded this piece of land. I can see them jarring along a rough corduroy road, the cedar logs that keep their wagon from sinking into the mud altogether rattling their bones and breaking the china the woman has packed so carefully into a wooden chest. She’s wearing a warm cloak, a bonnet tied tightly to her head, a heavy shawl wrapped around her neck. Her husband pulls on the reins and the oxen they’ve paid half their savings for comes to a halt.

Why are we stopping?

We’re home, wife, he says.

But there’s no home to be seen, just a wall of trees. And darkness is setting in. Surely those aren’t snowflakes.

I close the back hatch, climb in the car. No shrikes today. In fact, I’ve yet to see a shrike, though I did find a grasshopper impaled on a hawthorn last summer. Either it was a very unlucky jump or there are shrikes around here. I’m not giving up hope.

For information on Loggerhead Shrikes and a great photo of the elusive bird, visit Wildlife Preservation Canada’s website.